The Use of Special Operations Tactical Diving Vehicles:

An Historical Review and Its Contemporary Relevance

On November 1st 1918, during the last days of World War I (WWI), two men from the Italian Navy rode a primitive semi-submerged slow running torpedo into the heavily defended Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola. The men did not use breathing apparatus and thus had to keep their heads above the surface. As a consequence, they were observed and captured; but not before they had attached delayed initiation munitions (limpet mines) to the hull of two key targets. Approximately two-hours after being taken prisoner, muffled explosions were heard aboard the battleship Viribus Unitis, which subsequently sank fifteen-minutes later, together with the freighter Wien.

Despite its profound implications, the significance of two men sinking a Battleship was lost on the larger maritime powers of the time, such as the United Kingdom (UK) Royal Navy (RN) and United States Navy (USN), who were understandably focused on large surface capital ships as the central form of maritime capability. However, despite being an ally of Great Britain in WWI, Italy suspected it might one day have to confront the numerically superior British fleet, thus work began on developing a means of addressing this strategic imbalance. And so, throughout the 1930’s a small group of highly motivated visionaries within the Italian Navy, evolved the concept of operations first employed at Pola and pioneered a new form of maritime warfare that was to have a significant impact in the next world war that was soon to follow.

By the outbreak of World War II (WWII), in complete secrecy, the Italian Navy had developed the Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) along with the associated specialist equipment required to effectively prosecute a new form of maritime warfare. This military innovation employed the free-swimming diver as a covert underwater saboteur who was able to travel considerable distances using a submersible vehicle. Although surface swimmers had been used since ancient times to assault or to disrupt an enemy, this was a form of underwater warfare the world had not yet seen. Delivery of effect was executed using modified submarines carrying Dry Deck Shelters (DDS) to transport two-man vehicles or Chariots. Once at the objective area, the submarine would bottom out in shallow water and ‘frogmen’ from the top-secret unit Decima Mas (10th Light Flotilla), would lock out of the submarine using long endurance, closed circuit oxygen rebreathers. The DDS would then be flooded, opened and the Chariots pulled out onto the submarine casing. These were then ridden sub-surface to their objective by two Operators. Once at the objective area, a suitable target would be identified and they would descend under the target vessel. A front section of the Chariot containing 150kg of high explosive was then released and suspended beneath the ship’s hull before being prepared for later detonation. Each Chariot carried two such weapons for use against primary targets and small limpet mines for use against secondary targets.

Starting in 1940, these TTPs were first put into effect during a series of successful attacks against Allied merchant shipping located in the British controlled Gibraltar anchorage. Later in December 1941, three Decima Mas Chariots penetrated Alexandra Harbour in Egypt and managed to put the British battleships HMS Valiant and HMS Queen Elizabeth out of action for the remainder of the war. Prime Minister Winston Churchill described this attack as “the most strategic strike in the Mediterranean theatre”. Deeply frustrated at the UK’s lack of innovation in this field, he instructed Combined Operations, the organisation responsible for Commando raids, to do everything possible to replicate the Italian capability.

Having come to understand how these attacks were being prosecuted, Combined Operations and the RN embarked upon their own programmes to develop the TTPs and equipment necessary to undertake this new type of warfare. Once operational, the British quickly became very effective at it and later in the war, in an ironic twist of fate, following the Italian capitulation to the Allies, the British undertook joint ‘Chariot’ operations with the Italian Decima Mas against Axis forces in the Mediterranean.

In today’s Special Operations Forces (SOF) parlance, this capability is often referred to as Underwater Maritime Manoeuvre (UWM) and to a greater or lesser degree, is now a capability held by numerous nations worldwide. However, the origins of this can be directly traced back to that Italian attack at Pola at the end of WWI and the Decima Mas of WWII.

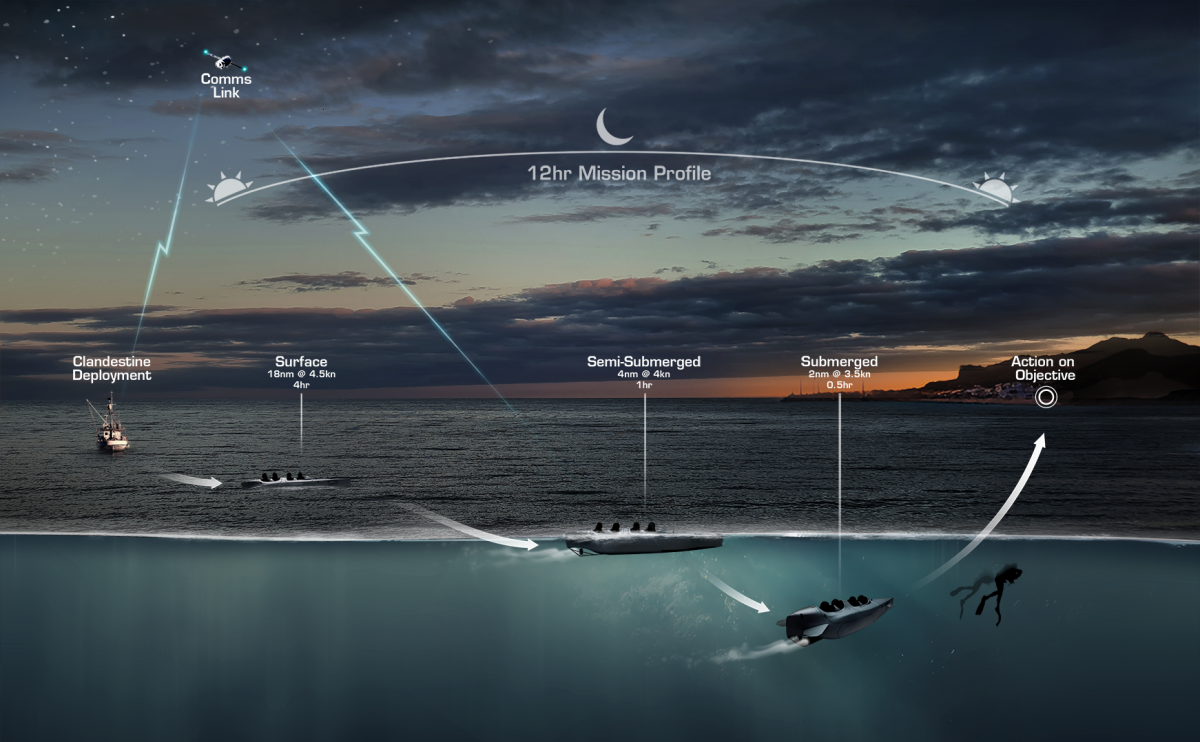

The list of specialist equipment and systems necessary for the prosecution of offensive maritime SOF operations is long and continually growing. However, the key means of projecting UWM capability is the Tactical Diving Vehicle (TDV). In WWII, this took the form of the Chariot, often referred to as the ‘Human Torpedo’, the motorised submersible canoe, colloquially named the ‘sleeping Beauty’ or the RN miniature submarine ‘X Craft’. Contemporary equivalents are the USN Mk 8 Swimmer Delivery Vehicle (SDV), the Shadow Seal hybrid TDV and the USN Dry Combat Submersible (DCS). There is however a hybrid vehicle with capabilities that differ notably from purely submersible TDVs. An example is the Carrier Seal that can travel hundreds of miles at high speed on the surface, run for extended distances semi-submerged and transit fully submerged carrying large payloads and weapon systems at speeds and for distances only dreamed of by WWII Charioteers.

Is then the penetration of an enemy harbour and the disabling or sinking of a key naval platform a realistic proposition today? If facing a non-peer adversary then the possibility is potentially very high. However, when facing a peer or near peer adversary, mission success probability reduces significantly. Not only is such a threat understood and likely to be anticipated, sophisticated passive and active diver surveillance systems are now able to detect and identify the various signatures that emanate from the human, underwater breathing apparatus and the TDV, automatically triggering defensive measures. However, not all harbours and anchorages are defended to such a degree. This potentially leaves targets of opportunity and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine demonstrates the vulnerability of naval vessels berthed or anchored in hostile waters away from the security of their home port.

Whilst attacks on poorly defended low-key targets may not have strategic effect, at a tactical level, such attacks cause disruption, confusion, navigational restrictions in confined waters and the re-allocation of enemy resource away from the front-line. In addition, success against such targets is a moral boost for attacking forces and the wider associated population, the positive psychological impact of which should never be underestimated during war.

If there is a low probability of a successful UWM strike against a peer or near peer strategic asset, what then is the reason for nations investing in such a capability? In reality, the classic ‘ship attack’ is only one of many operational scenarios. Maritime SOF mission profiles are broad and are continually evolving in response to the needs of modern warfare and national security interests. For example, such missions include Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition and Reconnaissance (ISTAR) operations, Maritime Counter Terrorism (MCT), counter narcotics, the infiltration, protection and exfiltration of Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) operatives, the covert deployment of SOF personnel across the littoral and into the hinterland, pre-amphibious landing beach reconnaissance and seabed warfare operations in navigation ‘choke-points’.

With geopolitical tensions driving a maritime pivot by NATO and her allies, what then is the future ‘direction of travel’ for this highly specialised form of warfare? It is widely acknowledged within the western maritime SOF community, that the focus on land activity over the last twenty-years has resulted in a number of littoral capability deficiencies. Modernisation priorities therefore include but are not limited to:

- Improved lethality & stand-off attack capability

- Increased UWM capability with greater range, speed and operational employment flexibility

- Signature reduction

- Sub-surface communications

- Electro optical sensor systems able to detect, recognise, identify, range and track objects of interest

- Improved sub-surface navigation

- Improved diver thermal protection

- Extended duration tactical life support systems with increased depth capability and duration

- The integration of un-manned surface and sub-surface systems into the SOF maritime battle space

- Improved situational awareness above and below the water-line.

Addressing these capability gaps requires significant investment and industry innovation in order to support the concept of the hyper enabled SOF Operator. At a unit level, whilst these technological challengers are being addressed, there is a transitional effort by many western maritime SOF organisations, to return to their roots through the re-establishment of a ‘waterborne’ culture. As a consequence, technology deficiencies are now being bridged and a stronger special operations maritime capability is being re-established.

The key to successfully achieving this operational re-focus, are TDV platforms that have the flexibility to project UWM capability in an effective and efficient manner, are employable across a broad range of mission profiles and operational scenarios, whilst enabling maritime SOF, where required, to undertake operations without the need for dependence upon large naval support platforms such as submarines and DDS systems.